Censorship and the Enola Gay

In an anti-DEI sweep of Department of Defense websites, the Enola Gay, the B-29 Superfortress that dropped the first atomic bomb on Hiroshima, is wiped from history.

The furor in the current administration over anything related to DEI resulted on March 7, 2025 in the removal from Department of Defense websites of images and references to the Enola Gay, the B-29 Superfortress bomber that dropped the first uranium atomic bomb, “Little Boy,” on Hiroshima on August 6, 1945. Its disappearance was in response to the publication of a list of words the current administration is attempting to censor in its reshaping of American English to fit its own ideological objectives.

According to the New York Times, among the targets are such commonplace words and phrases as: accessible, advocacy, all-inclusive (there goes your resort!), barrier, belong, bias, cultural heritage, disparity, diversify, equality (there go the founding documents of the U.S.!), female (but male is O.K., apparently), gender, historically (there goes my profession!), institutional, political, sex, sociocultural, underappreciated, and women (but “men” is O.K., apparently). Use of these words and phrases sends up red flags on government websites or in federal grant applications. The New York Times believes the list is actually longer. LBGTQ is on the list, but “gay” is not. Hmmm. Nevertheless, an important piece of history, one that was instrumental in marking a “before” and “after” in the history of the human race, disappeared from DoD websites: Enola Gay.1

The disappearance of the Enola Gay from DoD websites is part of the story of an authoritarian regime in the making.

The Enola Gay: From Construction to Museum Artifact

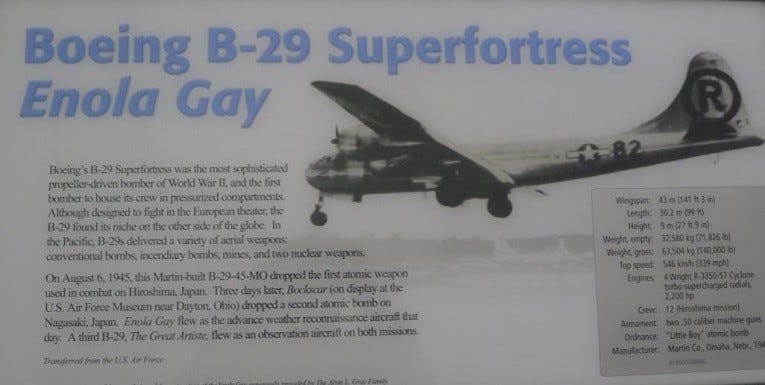

Col. Paul W. Tibbets, Jr., Commanding Officer of the 509th Composite Group assigned the task of dropping a new bomb over Japan, selected the B-29 he would pilot from a production line known as the “Silverplate” Superfortresses, which had been specially modified to carry the 10,000-pound bomb. The B-29 was the first fully pressurized combat aircraft. It had a range of 3,200 miles in combat and could fly at a top speed of 358 mph. It also was equipped with ground mapping radar, advanced communication technologies, enhanced targeting instruments (its gyroscopes could compensate for wind and its bombsight was the most precise available), and it could fly at just under 32,000 feet, higher than any other plane could in 1945.

The “Silverplate” model could deliver an atomic bomb because most of its guns had been removed (the tail ones remained) to accommodate the atomic bomb’s weight and because its bay doors had been modified for the drop. The plane was flown to Tinian in the Northern Mariana Islands (recently captured by the U.S.), where it was loaded with “Little Boy.” On August 5, 1945, one day before the flight to Japan, Tibbets named the B-29 after his mother, whose middle name was “Gay.”

In the wee hours of August 6, 1945, Tibbets took off for Hiroshima with a bombardier and navigator on board. Two other planes accompanied the Enola Gay—one with weather meters and other instrumentation (“The Great Artiste”) and the other for taking photographs (“Necessary Evil”). After the uranium bomb “Little Boy” was released, the plane had only a minute to turn, bank 155 degrees, and climb to avoid the cloud and the flash.

Detonating an atomic bomb at a predetermined height had not been tested beforehand. Of the 64 kilograms of uranium in the bomb, less than one kilogram (1.38%) went critical, yielding a blast of 15 kilotons. Somewhere between 130,00 and 140,000 people died. Three days later, Nagasaki became the second victim of an atomic bomb, this time the plutonium bomb “Fat Man.” Japan surrendered on August 15, 1945.

The Enola Gay had a storied history in the early atomic age after Hiroshima, having also participated as a weather data collection aircraft in the Nagasaki bombing. It was then flown to the Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands for the mid-1946 atomic tests of Operation Crossroads, but it did not drop any bombs. Subsequently, it was decommissioned and mothballed at a Smithsonian storage facility. It now can be seen at the National Air and Space Museum’s Steven Udvar-Hazy Center at Dulles International Airport in Virginia.

The aura surrounding the Enola Gay as an historical artifact was amplified by the controversy that surrounded President Truman’s decision to drop the bomb, a controversy whose first stage is epitomized by two opposing magazine articles from 1946 and 1947. The painful, graphic, and traumatic human side of the story—about the atomic bomb victims or Hibakusha—was told by John Hersey in “Hiroshima” in two venues. It appeared first as an entire issue of the The New Yorker in August 1946, and then shortly thereafter as a book published by Alfred A. Knopf, which was circulated free through the popular Book of the Month Club.2 Both sold out. Hersey’s telling of the human tragedy of the bomb raised questions about its morality and necessity.

Six months later former Secretary of War (1940-45) Henry L. Stimson penned “The Decision to Use the Atomic Bomb” for Harper’s Magazine. Calling the dropping of the bomb one of “the gravest decisions made by our government,” Stimson argued that the decision to do so was necessary to save American lives. He explained: “This deliberate, premediated destruction was our least abhorrent choice” in the face of plans to invade Japan in Operation Downfall, set to commence in November 1945, which would have meant the loss of thousands more American lives.3 (My father, John D. Olesko, who fought in the Philippines, was among those whose lives might have been saved by the bomb. Scheduled to participate in Operation Downfall, he instead became part of the occupation of Japan in the Nagasaki area.)

The controversy over the dropping of the bomb has played out in several venues since the Hersey and Stimson articles, none more vitriolic and consequential than the planned National Air and Space Museum (Smithsonian Institution) exhibition for the 50th anniversary in 1995 of the dropping of the bombs, in which the Enola Gay, as the key artifact, became the centerpiece of a heated historical debate.

The exhibit, entitled “The Crossroads: The End of WWII, the Atomic Bomb, and the Origins of the Cold War,” tried to treat a complex issue that had been around since 1945: the moral question of whether or not the United States was justified in dropping the bomb. It could have been one of the most important exhibits of the century: it could have analyzed the past, explore the vexing issue of why the bombs were dropped, and examined what happened afterward in light of the decision. It could have been America’s opportunity to come to terms with its past, as Germany had been doing for decades.4

But combining an object with a descriptive text, with words, was not so easy. NASM curators tried to give voice to the complexity of the historical issues surrounding the bomb, all with documentary foundations. The fight over the exhibit pitted museum curators (historians) against members of Congress, veterans, and survivors who wanted a different, and more decisive, historical description of the “good” war. The clash was one of history versus memory, and it demonstrated the political nature of interpreting the past.

The exhibit was cancelled, and the Director of NASM, Martin Harwit, fired. The final exhibit script (which was unused) presented the Enola Gay “without context, commentary, or physical reminders of the apocalyptic damage left in its wake.”5 And that’s pretty much the way the Enola Gay is exhibited in the Udvar-Hazy branch of NASM today where the script accompanying the plane describes it as an example of the B-29 Superfortress series, only mentioning the Hiroshima bombing later, but not as an event that changed the world.

The historical controversy continued for decades.6 It still has not ended. The National Security Archive at George Washington University has released in installments several new declassified documents covering the decision to drop the bomb, most recently in 2020. And Alex Wellerstein, of NUKEMAP fame, is working on a book on Truman and the bomb, a topic he explored in his blog on nuclear secrecy.

Lessons of the Erasure: Language and History in Authoritarian Regimes

Given the historical significance of the Enola Gay, why would the current administration have removed it from defense websites? Was it merely a misuse of AI? Or is some deeper issue behind it, such as the continuing reverberations of the ill-fated Smithsonian exhibit of the Enola Gay in 1995? Whatever the case, the attempt to erase the Enola Gay from history offers two lessons for the present.

The first concerns language. The political control of words and language is a feature of totalitarian and authoritarian regimes, including fascism, both real and imagined. In 1947 Victor Klemperer, the German scholar of Romance languages, analyzed the Nazis’ contortions of language in The Language of the Third Reich. Klemperer’s book addresses how Third Reich officials and administrators used language, including the creation of acronyms like GESTAPO (Geheime Staatspolizei, or secret state police), to acclimate the population to Nazi ideas, ways of life, and official actions to make them seem “normal.” Control over language was part of the Nazi state’s program of Gleichschaltung, the coordination and synchronization of society along the lines of Nazi ideology, including the removal of dissent and the opposition. Two years later George Orwell made the control of language a prominent feature in the fictional state of Oceania in his novel, 1984, which most Americans have read. In an appendix, Orwell explained that “Newspeak,” the official language of Oceania, “had been devised to meet the ideological needs of Ingsoc, or English Socialism.” Newspeak was an intentional suppression of certain words for political control: to narrow the range of what was possible to think.7

The current administration’s list of target words also aims to narrow what is possible to think, or even to act upon. It also has wiped out old acronyms, like DEI and USAID, and concepts like “climate change.” Gone, too, from the political arena at least, are the values associated with them, like equity, humanitarianism, and respect for the planet. They no longer define a political reality or guide human behavior.

Yet new acronyms or words have appeared. They create a new reality that, even when criticized, have to be used. Their use lends credence to, or even reifies, the new reality-in-the-making. A case in point is the use of “DOGE” as both an acronym for a supposed government agency and a word that designates a person in a high position of authority (e.g., Doge of Venice or even Doge of DOGE), whose etymology goes back to the Latin word dux, or leader. DOGE claims to promote efficiency, but at the moment all one sees is inefficiency, ruthlessness, callousness, carelessness, and ignorance of how the government actually works.

The second lesson concerns the public understanding of history. Recall that the Nazis created their own view of German history, one which led to the so-called “Thousand-Year Reich,” the Third Reich. The phrase is attributed to Hitler. In the fictional totalitarian and authoritarian regime of 1984, the party slogan was: “Who controls the past, controls the future; who controls the present controls the past.” Prescient words, indeed. Control of the past was a means of “reality control,” or in terms of Newspeak, “doublethink.”8

In the current administration the destruction of the past is apparent every day. The Enola Gay disappeared for strange reasons and without consideration of its historical significance, probably out of ignorance, but its presence has not been reinstated as of today. There’s more. USAID employees (the few that remain) were instructed to break the law and burn classified and personnel records in violation of the 1950 Federal Records Act, thereby erasing historical documentation and with it, the history based on them. These recent actions are totally within character for the current administration, whose petulant head is infamous for his rewriting of the historical narrative to fit his own views of past, present, and future.

Two of Yale historian Timothy Snyder’s twenty lessons in On Tyranny are “Be kind to our language” (#9) and “Listen for dangerous words” (#17).9 Following Snyder, Klemperer, and Orwell, an effective opposition has to both reject authoritarian redefinitions of words (including acronyms) and directly and openly question their “official” use. To do otherwise—to acquiesce or be just plain lazy—is to be complicit in the creation of the regime. Targeting words is a form of censorship that also censors forms of expression, including history. The story of the Enola Gay suggests challenges can work only if they restate the truth, including about the past.

The number of news organizations that have reported on this blunder is large, including: Daily Mail, Forbes, MSNBC-Rachel Maddow, NBC, New York Daily News, People, Rolling Stone, The Atlantic, and The Guardian. Rolling Stone really got it right: “Pentagon Flags WWII Plane that Nuked Japan as Woke: The Boeing B-29 Superfortress Bomber “Enola Gay,” which Dropped an Atomic Bomb on Hiroshima, Was Not, In Fact, Gay.”

Henry L. Stimson, “The Decision to Use the Atomic Bomb,” Harper’s Magazine 194 (no. 1161) (February 1947), 97-107.

As in the German Vergangenheitsbewältigung, or coming to terms with the past, customarily meaning the Nazi past.

Judgment at the Smithsonian, ed. Philip Nobile (N.Y.: Marlowe & Company, 1995), on xiv. The book includes the entirety of the original script for the exhibit (1-126) as well as a critical commentary by Barton J. Bernstein on “The Struggle over History: Defining the Hiroshima Narrative” (127-256).

For synopses of some of the debates, see: J. Samuel Walker, “Historiographical Essay: Recent Literature on Truman’s Atomic Bomb Decision: A Search for Middle Ground,” Diplomatic History 29 (No. 2) (April 2005): 311-334; and Peter Kuznick, “The Decision to Risk the Future: Harry Truman, the Atomic Bomb, and the Apocalyptic Narrative,” The Asia-Pacific Journal 5 (Issue 7) (July 3, 2007): 1-23.

Victor Klemperer, The Language of the Third Reich, trans. Martin Brady (London: Bloomsbury, 2013 (orig. 1947)); George Orwell, 1984 (N.Y.: New American Library, 1983 (orig. 1949)), especially “Appendix: The Principles of Newspeak,” 246-256.

Orwell, 1984, 32.

Timothy Snyder, On Tyranny: Twenty Lessons from the Twentieth Century (N.Y.: Tim Duggan Books, 2017).